Has the bond market run out of road as portfolio-diversification tool? No one knows for sure, but for some analysts the writing’s on the wall and markets are facing regime shift. The key catalyst: the long-running decline in current yield, which has gone negative in some countries and may soon do so in US.

At issue is whether it’s still reasonable to expect bond prices to rise when stocks take a beating. That’s been the historical tendency, but the usual routine is open for debate as current yields in the US approach zero.

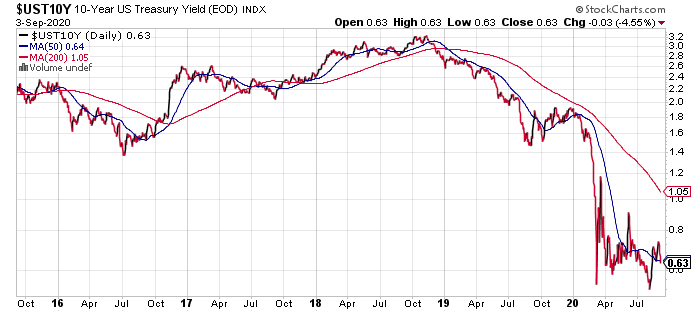

Consider the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield, which has fallen sharply this year and is currently a thin 0.63% (Sep. 3). That’s close to a post-World War Two low of 0.52% that was reached on Aug. 4, based on daily data published by Treasury.gov.

The notion that Treasury yields can continue to slide has confounded many investors—for years. After peaking at double-digit rates in the early 1980s, a long-term decline has endured for longer than many thought possible. Countless forecasts that anticipated the end of the slide have come and gone as yields have slipped further.

With the zero bound now within shouting distance there’s a new round of disbelief that the trend can persist. One common question: Why would anyone buy a 10-year Treasury that’s paying close to nothing?

Learn To Use R For Portfolio Analysis

Quantitative Investment Portfolio Analytics In R:

An Introduction To R For Modeling Portfolio Risk and Return

By James Picerno

One answer is that the demand for Treasuries is global and many of the obvious alternatives are already priced at negative current yields. The German 10-year bond, for instance, is trading at roughly a -0.50% yield and so the appeal of a US Treasury rate at +0.63% is compelling in relative terms to a foreign investor (even after factoring in forex risk).

There’s also a legacy issue to consider: the practice of buying US government bonds when risk-off sentiment spikes is a tough habit to break, in part because there’s still no substitute for the perceived safety and security of US Treasuries.

Ben Inker (head of asset allocation at GMO), however, thinks the end may be near for Treasuries fulfilling their historical role of providing offset to risk assets during times of crisis. He notes in GMO’s latest quarterly letter that in the coronavirus market crash in March it was telling that for 10-year bonds in countries with yields at or below zero the prices fell during Feb. 19-Mar. 23. By contrast, bonds with relatively high current yields performed as expected: delivering gains as stocks fell.

The implication: as US yields move closer to zero or go negative, the traditional diversification that these government bonds have provided in the past may fade, perhaps completely.

“The inimitable charm of government bonds over the last 30 years or so has been their wonderful tendency to give capital gains when the world starts to fall apart,” Inker writes. But that wonderful tendency appears to be at risk, he explains:

Today, the group of countries where short rates are already around zero or lower consists of every member of the G-10, the U.S. included. As a result, it seems to me unlikely that any government bond in the G-10 would provide meaningful positive returns if the global economy should encounter further problems associated with the Covid-19 outbreak or for any other reason in the near future. If short rates and bond yields rise meaningfully between now and that future downturn, that might no longer be the case. But if you are counting on such a rise occurring before the next downturn, you are also counting on bonds delivering a negative return in the interim.

An added complication: the Federal Reserve isn’t planning on dropping its target rate into negative territory. “I continue to think, and my colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee continue to think, that negative interest rates is probably not an appropriate or useful policy for us here in the United States,” Fed Chair Jerome Powell told CBS News in May. Future monetary stimulus, as a result, is likely to arrive in policies that are non-traditional – i.e., other than cutting interest rates.

The challenge for investors: asset allocation as traditionally conceived may not work as expected, and perhaps fail outright. The foundation has been the assumption that in times of crisis, government bond prices rise when stocks fall. If that’s no longer a reasonable expectation, a major rethink on asset allocation strategy is needed. Unfortunately, there are no silver bullets.

“There is no obvious simple replacement for government bonds that provides those valuable investment services,” Inker advises. “As a result, investors would be well advised to think critically about not only what their fixed income portfolios can feasibly achieve going forward but also what the implications are for the amount of risk they can afford to take across the rest of their portfolios.”

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report

There is a second chapter to this loss in diversification. One that has periodically popped up over the last couple years, notably in the winter ’18-19. At some point, as the Fed raises rates and yields spike up as a consequence, the overall return from bonds will diminish. At the same time investors will start exiting equities as they begin to envision a future when re-entering the bond market makes sense. The net effect will be a loss in both bonds and equities.

you say: “there is no obvious simple replacement ….”

There is one replacement that has worked for thousands of years…. GOLD !!!

Sylvain,

Yes, it’s a replacement, or at least one possible replacement, which is why I included it in a follow-up article:

http://www.capitalspectator.com/testing-alternatives-for-traditional-stock-bond-portfolios/

But it’s hardly a perfect replacement since gold comes with its own unique set of pros and cons for replacing bonds.

–JP