The manufacturing sector may be in recession, but the labor market still looks resilient. That’s the key message in recent economic updates. It’s anyone’s guess if this skewed relationship will endure, but for the moment it’s enough to keep the threat of recession in the category of a low-probability event, based on numbers published to date. With so much riding on payrolls these days, a stumble in job growth right about now would be a problem. But that’s not a real and present danger, according to yesterday’s weekly update on new filings for unemployment benefits.

Initial jobless claims fell last week, pulling back from a five-month high and settling at a seasonally adjusted 271,000. “Claims are staying at historically very low levels, which shows the labor market is pretty tight,” David Berson, chief economist at Nationwide Insurance, tells Bloomberg. “For the bulk of the economy, demand for workers is reasonably high. Companies are hesitant to let workers go.”

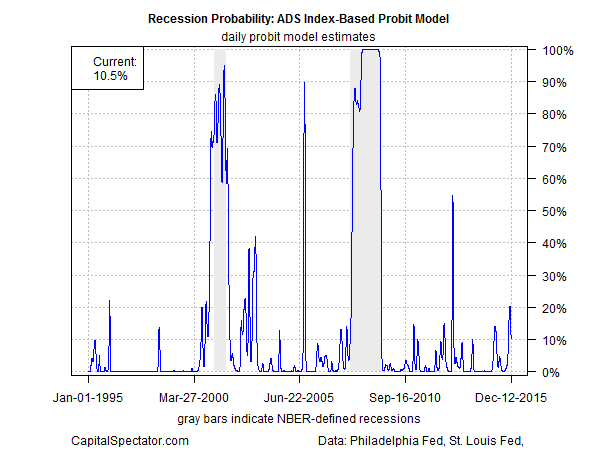

The upbeat news on claims pared the recent spike in the Philly Fed’s business cycle benchmark—the ADS Index. The implied probability of a new US recession from the vantage of this metric eased to low 11%, based on economic data for the period through Dec. 12.

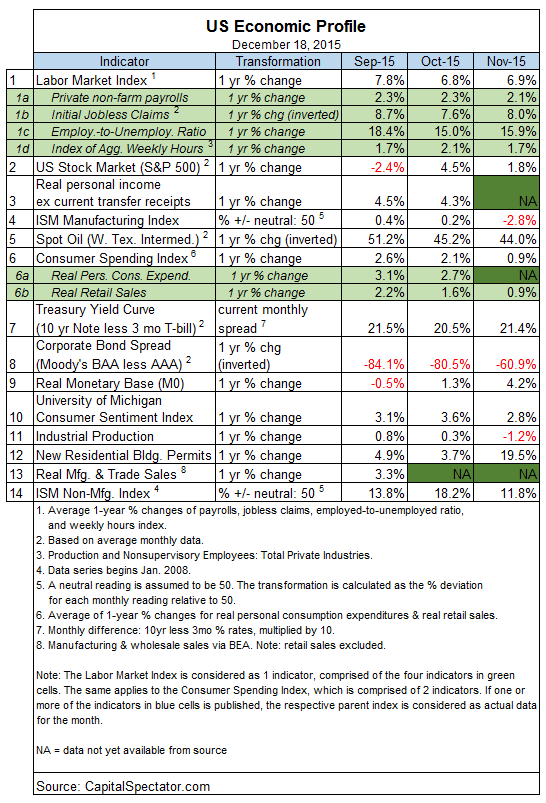

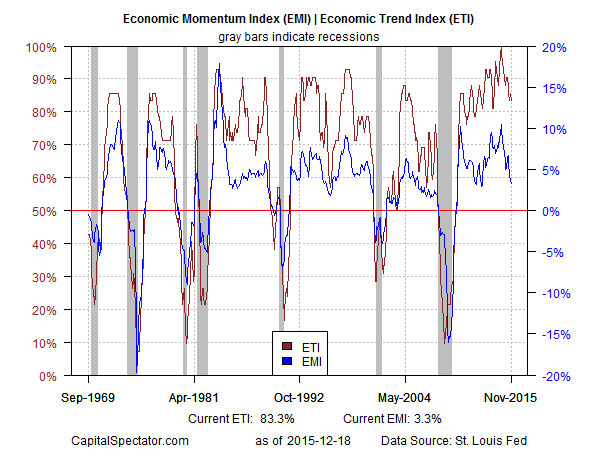

Economic risk is also low as of last month according to The Capital Spectator’s Economic Trend and Momentum indices (ETI and EMI, respectively), which track a diversified set of indicators. Near-term projections through January anticipate a slower macro trend, but at levels that remain well above the danger zone. The analysis is based on a methodology outlined in Nowcasting The Business Cycle: A Practical Guide For Spotting Business Cycle Peaks. Using this framework, an aggregate of economic and financial trend behavior shows that business-cycle risk remained low through November. The current profile of published indicators through last month (12 of 14 data sets) for ETI and EMI continue to signal a positive trend overall. The three exceptions in November: the corporate bond spread, the ISM Manufacturing Index, and industrial production. Otherwise, positive trending behavior rolls on.

Here’s a summary of recent activity for the ETI and EMI components and the various calculations that are used to generate the benchmarks:

Aggregating the data into business cycle indexes reflects positive trends overall. The latest numbers for ETI and EMI indicate that both benchmarks are well above their respective danger zones: 50% for ETI and 0% for EMI. When the indexes fall below those tipping points, we’ll have clear warning signs that recession risk is elevated. Based on the latest updates for November — ETI is 83.3% and EMI is 3.3% — there’s still a comfortable margin of safety between current values and the danger zones, as shown in the chart below. (See note at the end of this post for ETI/EMI design rules.)

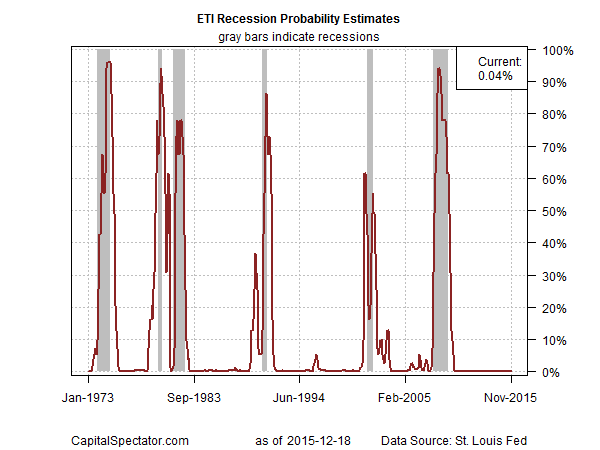

Translating ETI’s historical values into recession-risk probabilities via a probit model also points to low business cycle risk for the US. Analyzing the data with this methodology implies that the odds are virtually nil that the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) — the official arbiter of US business cycle dates— will declare last month as the start of a new recession.

For another perspective, consider how ETI may evolve as new data is published. One way to project future values for this index is with an econometric technique known as an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model, based on calculations via the “forecast” package for R, a statistical software environment. The ARIMA model calculates the missing data points for each indicator, for each month–in this case through Jan. 2016. (Note that Sep. 2015 is currently the latest month with a complete set of published data.) Based on today’s projections, ETI is expected to remain well above its danger zone for the near term. (Keep in mind that frequent business cycle updates are available on a weekly basis in The US Business Cycle Risk Report.)

Forecasts are always suspect, of course, but recent projections of ETI for the near-term future have proven to be relatively reliable guesstimates vs. the full set of published numbers that followed. That’s not surprising, given the broadly diversified nature of ETI. Predicting individual components, by contrast, is prone to far more uncertainty in the short run. The current projections (the four black dots on the right in the chart above) suggest that the economy will continue to expand. The chart above also includes the range of vintage ETI projections published on these pages in previous months (blue bars), which you can compare with the actual data that followed, based on current numbers (red dots). The assumption here is that while any one forecast for a given indicator will likely miss the mark, the errors may cancel out to some degree by aggregating a broad set of predictions. That’s a reasonable assumption via the historical record for the ETI forecasts.

For additional perspective on judging the track record of the forecasts, here are the previous updates for the last three months:

19 Nov 2015

21 Oct 2015

18 Sep 2015

Note: ETI is a diffusion index (i.e., an index that tracks the proportion of components with positive values) for the 14 leading/coincident indicators listed in the table above. ETI values reflect the 3-month average of the transformation rules defined in the table. EMI measures the same set of indicators/transformation rules based on the 3-month average of the median monthly percentage change for the 14 indicators. For purposes of filling in the missing data points in recent history and projecting ETI and EMI values, the missing data points are estimated with an ARIMA model.

Pingback: Manufacturing Could Be in Recession