The US economy appears resilient and vulnerable at the same time. There’s always uncertainty about the economy’s near-term path, but rarely has the data presented such a striking contrast in possibilities.

Let’s start with yesterday’s revision for third-quarter GDP. The Commerce Department upgraded growth to a 3.2% annual pace during the July-through-September period, up from 2.9% in the previous estimate. The improvement suggests the economy’s rebound after two quarterly declines has a strong tailwind.

Meanwhile, yesterday’s weekly update on jobless claims reaffirms that the labor market remains tight. New filings for unemployment benefits ticked up to 216,000 last week, but that’s still close to a multi-decade low. This leading indicator continues to suggest that US payrolls will continue to rise, and thereby blunt weakness in other areas of the economy.

But the feedback loop of good news is bad news is still in play. “The economy isn’t quite as close to death’s door as markets had thought,” says Christopher Rupkey, chief economist at FWDBONDS. “The Fed may well need to raise interest rates even higher in 2023 because the economy isn’t slowing so upward price pressures may persist.”

Oren Klachkin, lead US economist at Oxford Economics, has a similar view about the firmer Q3 GDP data. “The unexpected upward revision to Q3 GDP is encouraging but the economy will be tested soon from past tightening in financial market conditions and rate hikes by the Fed,” says Oren Klachkin, Lead US economist at Oxford Economics.

Another release on Thursday painted a considerably darker profile. The US Leading Economic Index’s (LEI) annual growth rate continued to slide deeper into negative territory in November, highlighting deteriorating economic momentum.

“Despite the current resilience of the labor market—as revealed by the US Coincident Economic Indicator in November—and consumer confidence improving in December, the US LEI suggests the Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening cycle is curtailing aspects of economic activity, especially housing,” says Ataman Ozyildirim, senior Director, economics, at The Conference Board. “As a result, we project a US recession is likely to start around the beginning of 2023 and last through mid-year.”

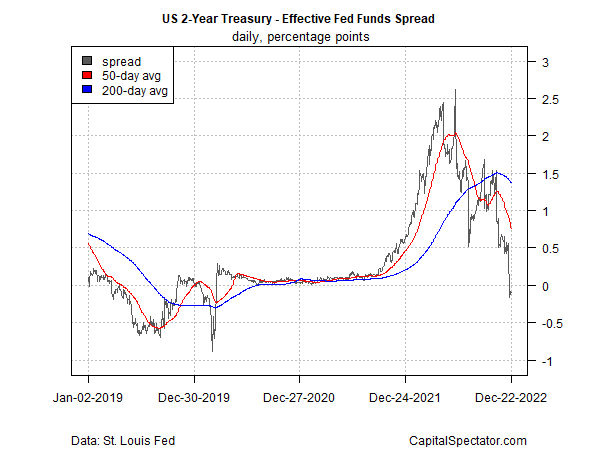

Bond and stock markets seem to be on board with a bearish outlook for the economy, despite signs of strength in the labor market. Notably, the policy-sensitive 2-year Treasury yield is now trading below the mid-point for Fed funds for the first time in nearly three years. The implication: the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes are close to peaking, if they haven’t already. The implied assumption: tighter monetary policy raises the risk that the economy will contract and the Treasury market is betting that the Fed will soon put its rate hikes on pause.

The stock market agrees that the macro outlook remains challenged, or so it seems based on the ongoing slide in the S&P 500 Index. Equities have suffered three failed rallies this year, largely due to bearish expectations linked to rate hikes and slowing growth.

The tricky part for markets is deciding if the central bank will go too far in hiking rates, which in turn will raise recession risk. The markets are pricing in relatively high odds that the Fed is committed to erring on the side of caution for taming inflation, which implies that economic risk will stay elevated.

The key variable is still incoming inflation data. If pricing pressure doesn’t fall fast enough in the months ahead to satisfy the Fed’s plans, more rate hikes are likely. In turn, that scenario will strengthen recession risk.

“The consensus is pretty clear that there is going to be a recession in 2023,” says Chuck Carlson, chief executive officer at Horizon Investment Services. “The issue is how much has the market already discounted a recession, and that’s where it gets a little bit thornier.”

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report