Fighting high inflation is tough enough, but the Federal Reserve’s been trying to tame pricing pressure when the economy is showing signs of weakening, at least in some corners. That’s a major challenge, but it’s even a bigger problem in the wake of banking turmoil triggered by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

The central bank normally eases monetary policy and cuts interest rates when economic risk is rising. Ditto for periods when a banking crisis threatens. But the usual policy tools aren’t available when inflation is high. In short, it’s a perfect storm for the Fed and one that may get worse before it gets better.

The key issue is that the policy tools the Fed can wield to tame inflation threaten to increase economic risk and exacerbate banking turmoil. The central bank, in short, finds itself between the proverbial rock and the hard place.

There are no good policy choices available. Rather, it’s a matter of choosing the least worst policy and hoping for the best. The current outlook is that while the SVB-triggered crisis has reduced the estimated probability of more rate hikes, the path ahead still appears set for more tightening due to ongoing inflation risk.

The Fed funds futures market this morning is estimating an 85% implied probability for a 25-basis-points increase at next week’s FOMC policy meeting. Market sentiment is no longer looking for a 50-basis-points hike, which prevailed before the SVB crisis. But futures are still pricing in another ¼-point hike in May.

The implication: the Fed will continue to prioritize inflation fighting. On that basis, deciding how much pressure lies ahead for the economy and the financial sector is closely linked with incoming inflation data. On that front the outlook is mixed.

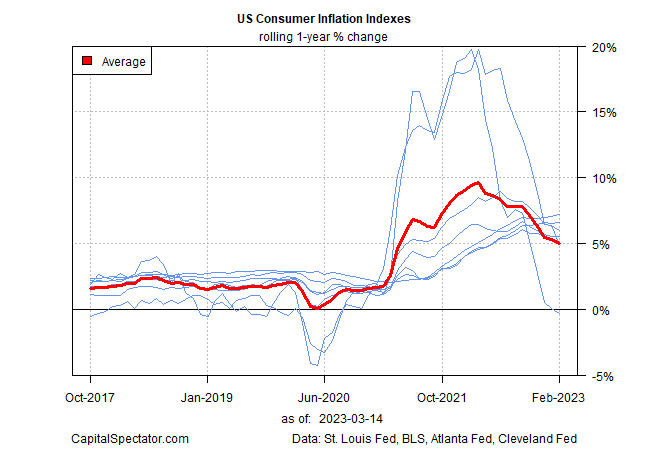

Let’s start with the good news: inflation has peaked. Consumer prices continued to ease on a rolling one-year basis through February. But the 6.0% increase for headline CPI and 5.5% for core CPI are still too hot for the Fed to declare victory. Indeed, the central bank’s 2% inflation target is nowhere on the near-term horizon.

The main problem at the moment is that inflation’s deceleration has been slowing and so the Fed’s policy tightening looks set to run longer than recently expected. In recent days there’s been speculation that the central bank will ease up on its hawkish bias. That’s a reasonable forecast, but the hawkish bias still looks set to roll on, albeit in a milder degree.

To be sure, the path ahead is much more fluid in the wake of the SVB collapse, but there’s still the elephant in the room: high inflation. Looking at several alternative measures of the inflation trend suggest that the optimistic scenario is that pricing pressure will fall to tolerable levels at some point in the summer (for details on the chart below see a sample copy of The US Inflation Trend Chartbook here).

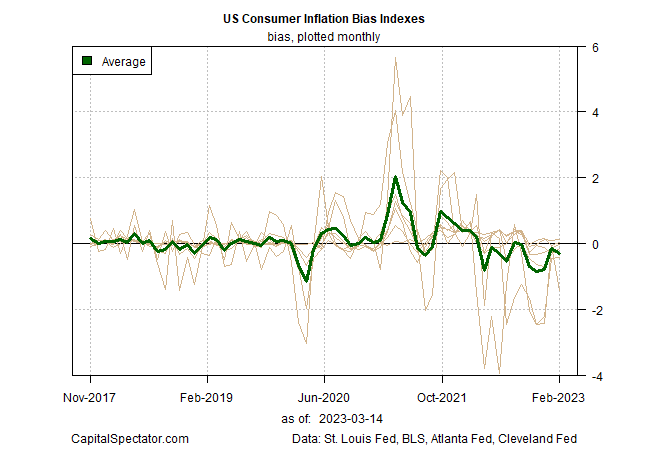

The risk is that the downside bias in inflation continues to weaken, as it has recently. The next chart below shows the monthly difference in the year-over-year changes in the one-year chart above.

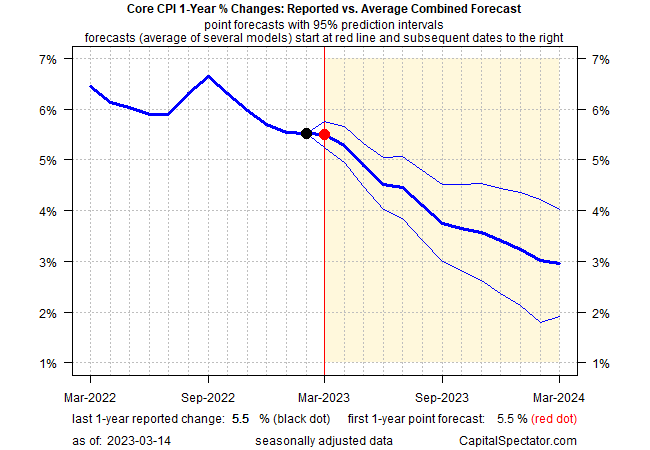

Yet there’s still reason for cautious optimism. CapitalSpectator.com’s ensemble forecasting model continues to project that core CPI’s one-year trend will ease further in the months ahead.

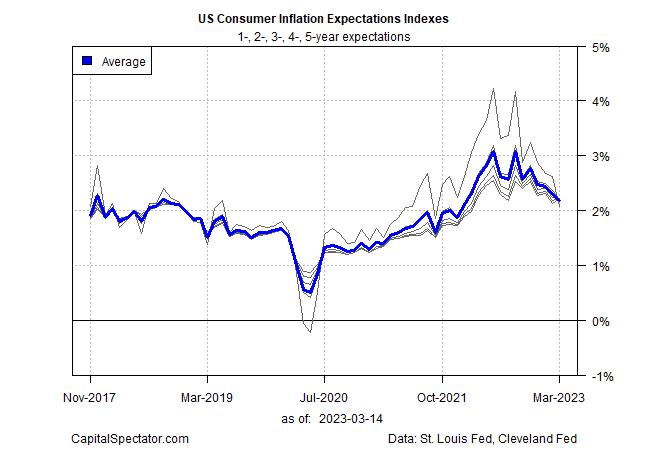

Meanwhile, inflation expectations are still trending lower, which will make the Fed’s job easier for reducing pricing pressure (based on estimates from the Cleveland Fed).

Ultimately, the most powerful inflation-fighting tool may kick in at some point: recession and/or a full-blown banking crisis.

The Fed’s goal, of course, is to tame inflation while minimizing blowback to the economy and the banking sector. Threading this needle is difficult even in the best of circumstances. The question is how quickly the challenge will ease, or not. The answer awaits in the incoming inflation numbers, along with how the risks for the business cycle and banking stress evolve in the weeks ahead.

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report