The inflation-is-transitory narrative took a beating in yesterday’s hotter-than-expected report for US consumer prices in May. Even after accounting for so-called base effects (temporary pandemic-related factors driving inflation higher), pricing pressure has accelerated.

It’s tempting to declare that the debate about the inflation trend is dead after reviewing the latest numbers on the consumer price index (CPI). But it’s still premature to conclude that a hotter inflation regime that persists is now an enduring feature of the US economy. Granted, that risk is higher than it has been in recent years. But it’s unclear how tenacious the ramp-up in pricing will be as the country continues to transition from a pandemic shutdown to something approximating “normal” conditions.

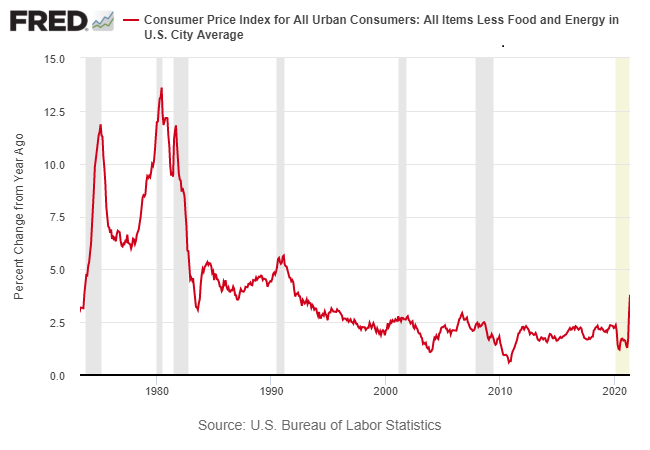

Taking the numbers at face value, however, certainly looks worrisome. Consider the surge in the rolling 12-month change in core CPI, which strips out food and energy prices. (Core CPI has proven to be a more reliable measure of the inflation trend vs. headline CPI, which includes food and energy, and so we’ll focus on it here.) In May, this gauge of inflation shot up to 3.8%, a 29-year high.

By some accounts, the latest report is the smoking gun that confirms the worst fear: inflation has ramped up and will remain so for the foreseeable future, perhaps rising further. The counterargument is that pandemic effects are still in play and so the recent upside volatility in CPI data may be misleading. That’s the view of the Federal Reserve and, for the moment, some degree of private economists.

“A lot of the surge in prices are for things that are just normalizing,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. As examples, he points to prices for “hotels and rental cars and used vehicles, sporting events, restaurants. Everyone is just getting back to normal, so pricing is just returning to what it was pre-pandemic.”

Perhaps, but there are more than base effects at play in the recent rise in inflation. Nonetheless, it’s still unclear how strong and persistent economic activity will be once the macro trend fully normalizes. In turn, getting a clear read on inflationary pressure will remain unusually challenging for several months at the least.

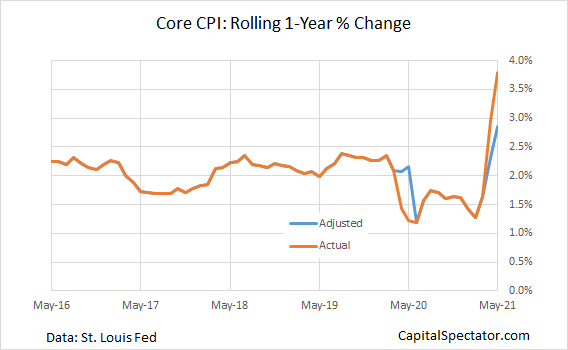

As a thought experiment, let’s imagine that last year’s pandemic-triggered deflation never happened and consider how core CPI’s one-year trend would have evolved in that alternative scenario. There are several possibilities for estimating such a scenario and so a high degree of subjectivity risk lurks. But let’s throw caution to the wind and assume that the monthly deflation episodes in April and May 2020 never happened. Instead, we’ll use the previous six-month average of monthly inflation (based on Oct. 2019-Mar. 2020) to replace the two deflationary months. Not surprisingly, calculating the 12-month rolling percentage change for core CPI with the adjusted numbers reflects a softer increase through last month: 2.8% vs. 3.8% that was reported.

Even with this adjustment, however, inflation picked up substantially. The question is whether the acceleration – even after accounting for base effects – is related to the economy’s reopening or effects that’s longer-lasting?

Although some analysts insist that they know the answer with certainty, reality still leaves room for debate. For example, will faster economic growth fade as government stimulus recedes? What happens to growth and inflation if the Federal Reserve decides to start tightening monetary policy? Is the economy strong enough to sustain higher rates? If not, could the Fed trigger a recession by raising rates? Meantime, will coronavirus variants create a new wave of infections and fatalities in the fall and winter?

There are many unknowns lurking in the months ahead. The first order of business is comparing the May data with inflation numbers published over the summer with an eye on deciding if the recent surge is peaking.

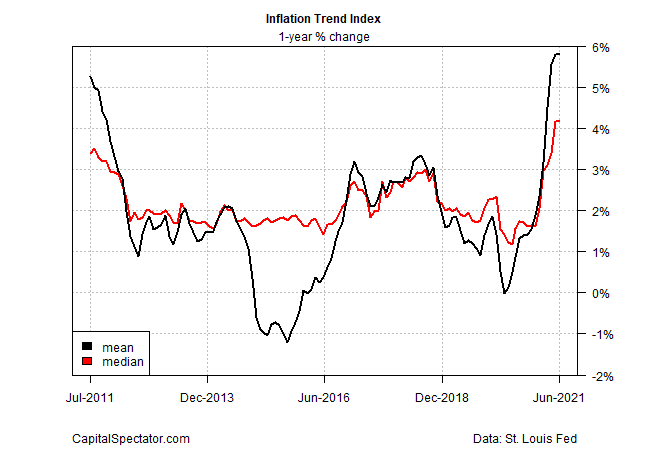

Revised data for the Inflation Trend Index, a seven-factor benchmark that’s designed to provide a degree of forward guidance on the directional bias of pricing activity, continues to suggest that June will mark the high point for the current run of accelerating inflation.

Nonetheless, the US economy remains in an unusually volatile and fluid period, with no clear precedent in modern history. Accordingly, there’s more guesswork involved than usual for peering into the future. That opens the door to seeing whatever you want to see. The good news: there’s only one set of incoming numbers. Unfortunately, the results will still trickle in slowly, one report at a time. It’s going to be a long, data-dependent summer.

Learn To Use R For Portfolio Analysis

Quantitative Investment Portfolio Analytics In R:

An Introduction To R For Modeling Portfolio Risk and Return

By James Picerno