China has long been a reliable source of growth for the global economy, but that reliability is looking increasingly shaky.

As the world’s second-largest economy, China’s fortunes cast a long shadow and so the recent headwinds deserve more attention. This week’s news that the country’s GDP rose more than forecast was greeted with sighs of relief, but some analysts advise that slowdown risk is rising.

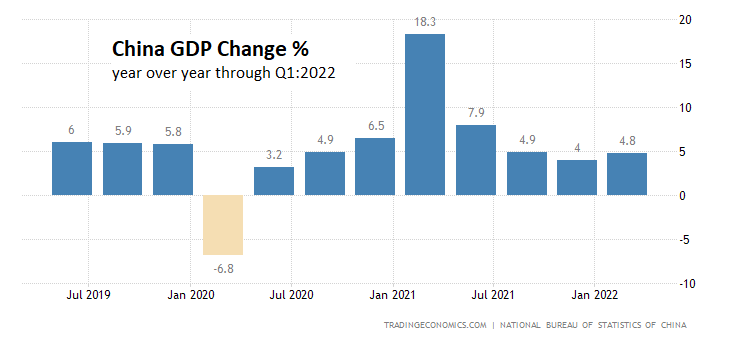

China’s GDP rose 4.8% in this year’s first quarter on a year-over-year basis, up from 4.0% in the previous quarter. A closer look, however, suggests that trouble brewing. Retail sales, for example, fell 3.5% in March from the year-earlier level—the first slide in nearly two years.

Most forecasters still expect China’s growth engine to remain intact for the near term, but at a relatively modest, decelerating pace. The government’s growth target for this year is roughly 5.5%. That’s a strong gain by standards in the West, but for China it marks the softest increase in three decades. In fact, a 5.5% increase for 2022 looks increasingly unlikely as the country struggles with multiple challenges.

The government admits that the road ahead will be rocky. “We must be aware that with the domestic and international environment becoming increasingly complicated and uncertain, the economic development is facing significant difficulties and challenges,” China’s National Bureau of Statistics said in statement on Monday.

Although Q1 GDP data was better than expected, some analysts are predicting that Q2 may be less forgiving. One clue is the rising unemployment rate in 31 major cities in China.

“This indicates the unemployment problem in the large cities has become more severe than when the Covid pandemic started in 2020,” says Zhiwei Zhang, chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management. “The Covid outbreaks only forced Shanghai and some other cities to enter lockdowns in late March and early April. Therefore the economic slowdown likely worsened in April.”

Analysts at Societe Generale, a bank, warn that China’s economy “is in distress. The problem, as we have repeatedly stressed, is the lockdowns — still in place and still spreading.”

Nomura China chief economist Ting Lu and his team agree. In a research note sent to clients they estimate that the Chinese economy “most likely” contracted in April. “Amid expansive lockdowns, logistics disruptions, the downward spiral in the property sector and slowing exports, we expect activity data to tumble in April, and gauge that the risk of recession has been rising in Q2.”

A key question is how much China’s government can offset decelerating growth with fiscal and monetary support? Another critical variable is whether the government continues to pursue a zero-Covid policy, which contrasts with much of the rest of the world, which is increasingly learning to live with the virus. By some accounts, the longer China tries to stave off widespread infection, the bigger the eventual blowback when the policy is abandoned, as some analysts predict.

“Further impacts from lockdowns are imminent, not only because there has been a delay in the delivery of daily necessities, but also because they add uncertainty to services and factory operations that have already impacted the labor market,” says Iris Pang, China chief economist at ING. “We may need to revise our GDP forecasts further if fiscal support does not come in time.”

An analyst at Reuters’ Breakingviews division advises that the zero-Covid policy puts China at risk of a “self-inflicted recession.”

But not everyone agrees. While the economy is struggling, it’s “not in serious trouble,” according to Derek Scissors, chief economist at China Beige Book, a consultancy. “We’re not looking at outright contraction as China suffered in 2020,” when the pandemic was raging.

The optimistic narrative is that once Beijing has the current Covid-19 outbreak under control, the government can fully refocus on supporting the economy through fiscal and monetary stimulus. “There’ve already been some signs that the government is aware of the risks here [and] there’s been more talk about policy support,” says Richard Yetsenga at ANZ, an Australian bank.

A possible joker in the deck is China’s inability to contain the current outbreak. In that case, the relatively upbeat expectations for China’s economy could quickly turn to dust, which would have implication for an already strained global economy, courtesy of stronger headwinds thrown off by the Ukraine war.

“The pandemic has to be the biggest source of risk for China’s growth this year,” says Zhennan Li, chief China economist at AllianceBernstein.

Exactly how big a risk is still open for debate. The critical variable is deciding how much faith to put in China’s efforts to do what no other nation has achieved: stamping out the spread of Covid-19.

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report