The US was supposed to be in recession by now, according to numerous forecasts from early in 2023. But the bearish forecasts have fallen flat as output has remained positive. In fact, GDP surged in the third quarter, dealing a body blow to expectations that a downturn was imminent. But rather than admit defeat, the recession forecasters have simply moved forward the expected tipping point.

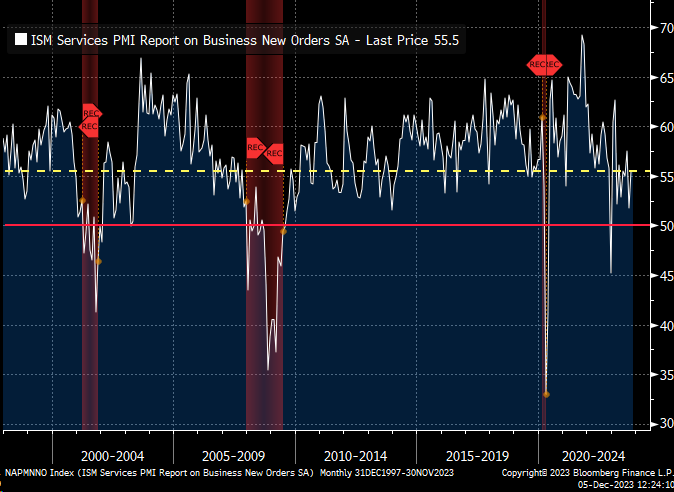

The latest narrative making the rounds: the weakness in new manufacturing orders for November – via ISM survey data – points to high recession risk. As one analyst observed in a post on X this week: “there’s never been a #recession with ISM New Orders (#LEADINGIndicator) at 55.5.”

This indicator may, or may not, be a high-confidence estimate of business-cycle risk, but it’s hard (impossible) to say. Ditto for using any one indicator (or even two or three) for estimating the likely odds in real time that an NBER-defined recession has started or is imminent.

What is known is that manufacturing’s track record as a timely – some would say reliable – source for estimating recession risk has stumbled in recent years. That doesn’t mean we can ignore this data – far from it. But it’s yet another reminder that periodic failure for any one indicator, no matter it’s track record, is inevitable. Par for the course.

All of which brings us back to a recurring theme on CapitalSpectator.com: there’s only one way to generate timely and relatively high-confidence estimates of recession risk in real time – develop a methodology that uses a carefully selected, diversified set of indicators. Every indicator suffers false signals at times. Although that risk can’t be sidestepped entirely, it can be engineered down substantially with a multi-factor methodology.

What’s the downside? A multi-factor methodology is more reliable, but will be “late” vs. whatever the hot indicator is at the moment. The challenge is that no one really knows which lone indicator will prevail as superior through time. Indeed, this list keeps changing. The art/science of recession nowcasting is balancing timely signals with reliable signals. Finding the sweet spot that maximizes each — simultaneously — is the goal. What’s clear is that you can’t reach that goal with one indicator.

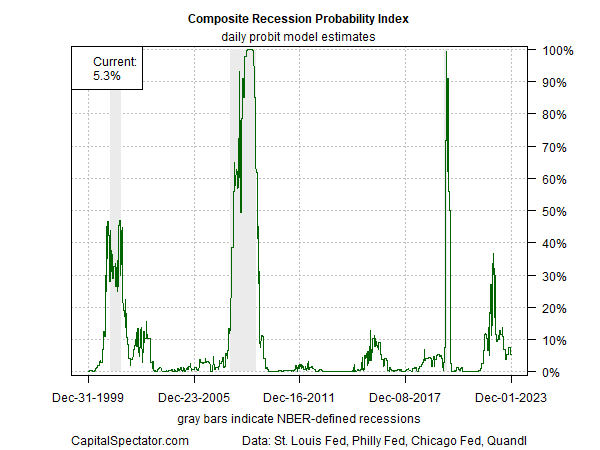

On that note, the latest weekly update of The US Business Cycle Risk Report continues to reflect low recession risk (through Dec. 1). The newsletter’s main indicator – Composite Recession Probability Index (CRPI) – estimates a roughly 5% probability that an NBER-defined downturn is in progress. (For details on the methodology, see the sample edition of the newsletter here.)

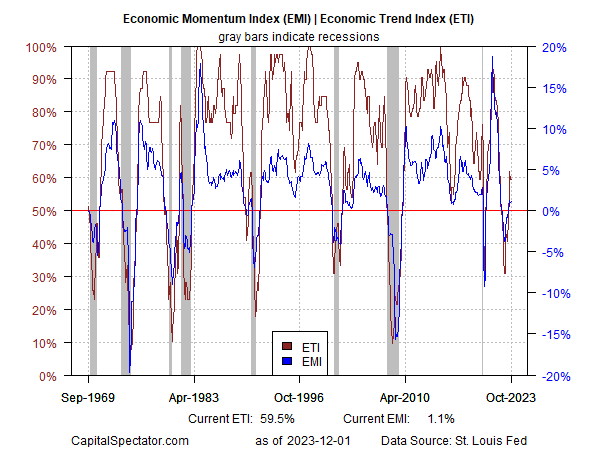

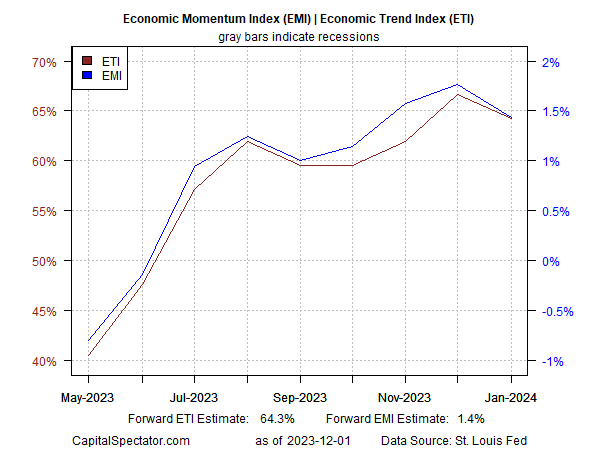

Another set of propriety indictors that look ahead by 2-3 months (the longest window possible for maintaining a relatively high-confidence estimate) point to an ongoing expansion through January. The multi-indicator Economic Trend Index (ETI) and Economic Momentum Index (EMI) benchmarks have been reflecting a rebound in economic activity for much of this year – see this update from May, for instance. Fast forward to the current profile and the numbers still skew positive in a moderate degree, as the chart below shows — both indicators are above their respective tipping points (50% and 0%) that indicate recessionary conditions.

Using an econometric toolkit to develop near-term forecasts for ETI and EMI through January tell us that the expansion will likely endure through the start of the new year.

Is a recession later in 2024 possible? Of course. Is it likely? That’s a tougher question. There are many methodologies for guesstimating what might happen by, say, June 2024. But let’s be clear: looking beyond a 2-3 months window is guessing.

That leaves us with a simple but effective rule that’s proven durable through time: in pursuit of time and relatively high-confidence recession nowcasts/forecasts, there’s no substitute for aggregating a wide variety of carefully selected indicators that capture the key drivers of the economy’s trend.

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report