New York Fed President William Dudley is inclined to ignore the recent drop in inflation forecasts via the Treasury market. In a speech last week, he explained that “in assessing inflation expectations, I currently put more weight on survey-based measures of inflation expectations as opposed to market-based measures.” The distinction is more than academic. “Survey-based measures have been generally stable, consistent with inflation expectations remaining well-anchored,” he noted. Market-based estimates, however, tell a different story.

The yield spread for a nominal 10-year Treasury less its inflation-indexed counterpart dipped to a three-year low yesterday (Nov. 18). Mr. Market’s inflation estimate is now a slim 1.84% — down from nearly 2.30% as recently as this past July. Surveys may reflect a well-anchored outlook for inflation, but the Treasury market seems to be anticipating a stronger run of disinflationary momentum.

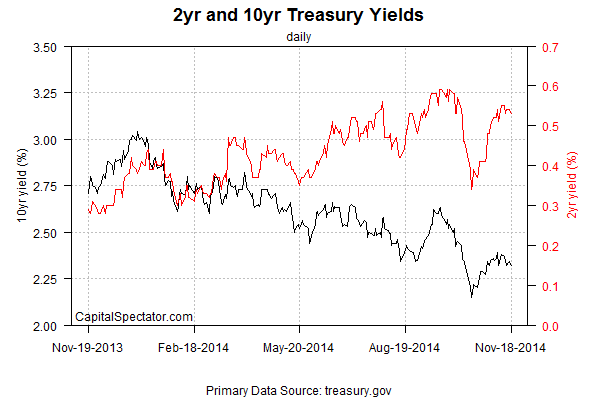

The slide in inflation expectations comes at a time when the Federal Reserve is signaling that it’s still planning to raise interest rates at some point next year. Although Treasury yields have climbed in recent weeks after last month’s stumble, the overall trend for the year still reflects a downward bias. The benchmark 10-year yield yesterday (Nov. 18) settled at 2.32%, down from 3.04% at last year’s close.

It’s the new conundrum: falling yields and lower market-based inflation expectations in the face of expectations for a rate hike in the near term. It’s an odd situation, and it comes with a fair amount of risk. As Bloomberg observes:

The stakes are higher this time because rates are lower and the yield curve is flatter. Raising short-term rates in the face of stable or falling long-term rates could lead to a situation where the Fed “quickly inverts the yield curve and turns credit creation on its head,” said Tim Duy, an economics professor at the University of Oregon in Eugene and a former U.S. Treasury Department economist.

An inverted yield curve occurs when short-term securities yield more than longer-dated bonds. That discourages banks from extending credit because they finance long-term loans with short-term debt. Inverted yield curves typically precede recessions.

Duy said the Fed has few options if long rates don’t rise after increases in the federal funds rate: the Fed would have little scope to raise the benchmark further, and not much room to cut if the economy were to slump.

“I’m sort of wondering, what’s the game plan here,” Duy said.

Part of the explanation for the divergence between expectations for a rate hike and lesser current yields is bound up with the global appeal of Treasuries at a time of heightened worries of an economic slowdown. The US economy (so far) continues to show a healthy degree of forward momentum, but deceleration, stagnation or worse dominates the macro news for other key economies. Europe is stagnating at best while Japan has slumped into a new recession. A pair of large emerging markets—Brazil and Russia—are contracting too. China’s economy is still growing, and at a strong rate by developed-market standards, but the expansion has decelerated recently. China is “the thousand-pound gorilla in the emerging world and a big, big question mark,” advises Nariman Behravesh, chief economist at IHS.

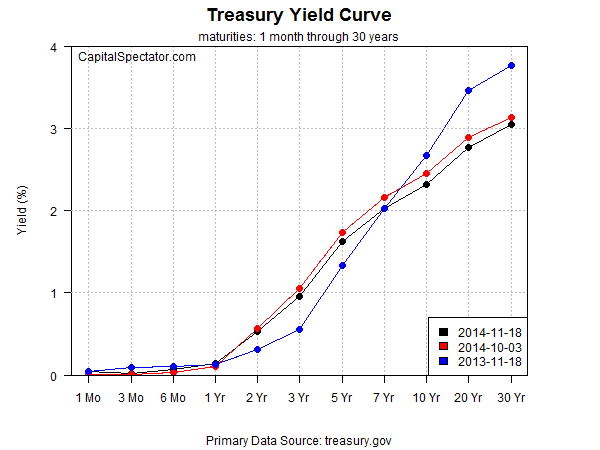

Fresh concerns about the global economy are once again elevating the appeal of bonds denominated in the world’s reserve currency. Treasuries, in short, are priced for reasons that reflect a mix of US and global macro expectations. It’s a muddled affair at the moment, but the net result clear: the crowd is bidding Treasury prices up, which of course pushes yields down, albeit primarily at the long end of the yield curve.

The bulk of the latest drop in Treasury yields has been restricted to maturities at 10-years-plus relative to year-ago rates. By contrast, yields for maturities between two and five years are still modestly higher as of yesterday relative to year-earlier levels.

Eventually, the conundrum will be sorted out with the arrival of new data. Meantime, the key questions:

1) Will the US economy continue growing while the trend elsewhere deteriorates?

2) Will the global slowdown ex-US turn into a full-blown recession overall?

For now, the US macro trend remains encouraging. The outlook for the rest of the world overall is challenged, but it’s not yet obvious that a global recession is fate. “The start of the final quarter saw global economic growth slow for the third straight month,” according to the October update of the J.P.Morgan Global Manufacturing & Services PMI.

Growth, in short, still has the upper hand overall, albeit in a decelerating degree. It’s premature to assume the worst, but Mr. Market is inclined to hedge his bets, as implied by the mixed messages in the Treasury market of late. The optimistic view for the US is that it can decouple from any troubles abroad. So far, that’s a reasonable assumption (until or if the US numbers tell us otherwise). But even if the American economy remains resilient in the face of foreign weakness, the Treasury market will continue to reflect a global outlook.

As a result, analyzing the yield curve is complicated these days. Untangling the outlook for the US from the rest of the world is a messy business. As Dudley noted last week, “growth and stability abroad makes all our jobs easier.” Unfortunately, those two attributes are in short supply beyond the US.

Pingback: Wednesday links: consistent outperformers | Abnormal Returns