In its first week in office, the Trump administration has reaffirmed that trade agreements are in the crosshairs. The Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) was the first victim. Trade between Mexico and the US appears to be the next domino to fall. The US stock market, so far, doesn’t seem to have a problem with the rise of anti-trade actions and rhetoric in Washington. But the slowing and perhaps the reversing of the decades-long policy of embracing free trade comes with risks for the US economy.

The White House yesterday floated the idea that the US may impose a 20% tax on imports from Mexico, although the administration subsequently added that such a tariff is only one possibility under consideration as a means to pay for a border wall between the two countries. Nonetheless, there’s been a clear shift in the government’s trade priorities since Trump has taken up residence at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, with huge economic stakes hanging in the balance.

Consider a few facts, starting with the reality that roughly 6 million US jobs are tied to trade with Mexico, according to the US Chamber of Commerce (USCC). A few other items to consider, via USCC:

● Since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) entered into force in 1994, trade with Canada and Mexico has risen nearly fourfold to $1.3 trillion in 2014, and the two countries buy more than one-third of all US merchandise exports.

● US merchandise exports to Canada and Mexico rose by 66% over just the 2009-2014 period, reaching $552 billion in 2014. In fact, our North American neighbors provided 39% of all growth in U.S. merchandise exports in the same period.

● US merchandise exports to Mexico (population 128 million) were nearly double those to China (population 1.4 billion), which is the third largest national market for U.S. exports.

●The US in 2014 had a trade surplus in manufactured goods ($21.6 billion) with its NAFTA partners.

Overall, a sober, fair-minded analysis of NAFTA reveals that free trade between the US, Mexico, and Canada has been a win-win. No trade agreement is perfect, and so there are many aspects of NAFTA that can be improved and arguably should be. But the past several days don’t provide much encouragement for thinking that a productive renegotiation is at hand. Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto yesterday cancelled a scheduled meeting with Trump after the President’s comments on building a border wall. Not exactly the start to a beautiful trading relationship.

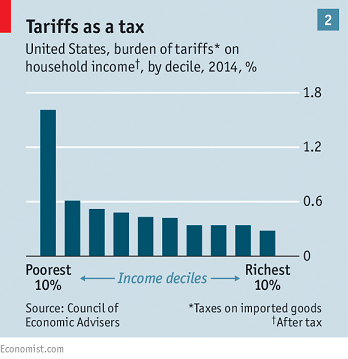

The cold, hard reality is that Mexico is one of the top trading partners for the US, with millions of US jobs linked to the relationship. Meanwhile, the idea of raising the price of imports by a fifth will, to a degree, force American consumers to pay higher prices. And as The Economist reminds, trade tariffs tend to hit the poorest citizens the hardest, based on research by the Council of Economic Advisers.

While there’s a case for renegotiating NAFTA, the Trump administration’s initial efforts appear designed only to bury the trade agreement. In the process, a centuries-long process of promoting free trade, which begins with Adam Smith’s treatise on the topic in 1776, may be peaking.

If so, some of the blame can be laid on free-trade proponents. It’s always been clear that while trade is usually a net positive for economic growth, there are losers as well as winners. While the winners tend to outnumber the losers by a wide margin, the victims of globalized free trade haven’t been fairly compensated. But that’s a policy failure rather than a case for gutting free trade.

In any case, the US now seems bent on fomenting a trade war with Mexico, which may be a prelude to similar actions across the globe. Although the economic implications are worrisome, it’s unclear how the blowback will unfold. For the moment, the US stock market shows few signs of concern and seems to assume that the price tag will be minimal. The S&P 500 is just below an all-time high.

Meanwhile, history’s trade lessons via the disaster known as the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 appears to have resonated with at least one member of the Trump administration. It “didn’t work very well, and it very likely wouldn’t work now,” Trump’s commerce secretary, Wilbur Ross, said in his confirmation hearing.

But with populist political movements on the rise in the US and elsewhere, the arc of expanding global trade that’s prevailed for much of the past half century may be in retreat. That doesn’t mean that big changes are imminent – renegotiating (or dismantling) the architecture of trade that took decades to build won’t happen overnight. Ditto for any blowback.

Change, however, appears to be coming. For those who argue that reversing the free-trade trend is a positive for the US, it’s all good. History, and an overwhelming consensus of economists, argue otherwise. But for the first time in decades, none of that seems to matter.

“Most people I talk to tend not to think a trade war is the base-case scenario — they treat it as a black swan event,” Hao Hong, an analyst at Bocom International Holdings in Hong Kong, tells Bloomberg. “I think the possibility is much larger.”

The key question: Does Donald Trump agree?