Maybe, but the current pace of wage increases for workers in the US–even after the pop reported in January’s payrolls data–still implies inflation at a rate that’s well below the Fed’s 2% target. Nonetheless, analysts are becoming more confident that the latest round of employment numbers boosts the odds that the Fed will begin raising interest rates later this year, perhaps as early as June.

The faster rise in wages in the January jobs report was widely cited as a factor that could trigger a new phase of monetary tightening. Mr. Market appears to be on board with that forecast. The 2-year Treasury yield—widely considered as the canary in the coal mine for rate expectations—jumped on Friday to 0.65%, which amounts to the biggest daily increase in five years. But to the extent that expectations for a rate hike are based on higher inflation that’s fueled by wage increases, the latest numbers still look unconvincing.

Even so, a number of media reports on Friday pointed to what some suggested is a smoking gun: the annual increase in average hourly earnings for all employees, as reported in the monthly payrolls release. On first glance, it’s tempting to see this measure of wages as signaling higher inflation and a relatively early rate hike. The year-over-year change for wages increased to 2.2% through last month—up from December’s 1.9% gain. But when we look at this metric in historical context, the latest 2.2% advance doesn’t look extraordinary. In fact, the latest advance amounts to a sluggish pace that continues to bounce around in a relatively low range.

Keep in mind that the “all employees” measure of wages has a limited history, dating to 2006. For deeper analysis of the relationship between wages and inflation we can turn to a comparable benchmark with a longer history–the Labor Department’s hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory employees (PNE-EARNINGS), a data set that stretches back to 1964. But here too the latest annual increase—up 2% through last month–remains at the low end of comparisons in recent years.

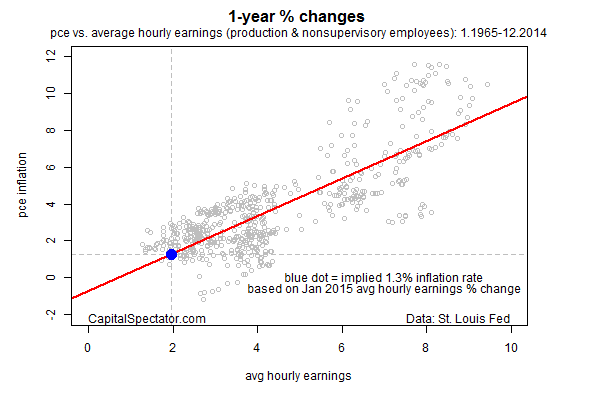

Analyzing the 50-year relationship between annual changes in PNE-EARNINGS and the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE)—the Fed’s preferred inflation benchmark–with a linear-regression model implies a 1.3% rate of inflation. Although that’s higher than the actual annual change in PCE inflation of 0.8% in the December report for spending and income, a 1.3% inflation rate is still well below the Fed’s 2.0% target.

The implied inflation rate rises a bit, to 1.4%, if we use core PCE, which strips out food and energy prices for what is arguably a superior measure of pricing pressures. But the general message is unchanged: inflation is still on track to run well below the Fed’s target for the near-term future.

The key takeaway is that recent improvements in the number of jobs created has yet to make a material impact on wage growth, which remains sluggish by historical standards. Wages rising at roughly 3% or higher on an annual basis would align with inflation at 2%. But there’s no sign of those levels in the latest data. That doesn’t mean that the Fed won’t start raising rates at some point this year. But if you’re basing your forecast for a rate hike on the historical connection between wages and inflation, the supporting data still looks pretty thin at the moment.

Pingback: 2.2 % Wage Growth Indicates Inflation Still Below Fed Target

Pingback: 02/09/15 - Monday PM Interest-ing Reads -Compound Interest Rocks

Pingback: Tuesday Morning Links | timiacono.com