Trends are among the most powerful forces in economics and finance, but every trend plants the seeds of its own reversal. If prices rise (fall) enough, the trend reverses. Forecasting these reversals is tricky, mostly because of the complication and chaos unleashed by the feedback loops that infuse markets and economies.

In the current environment, commodities prices are the main event for monitoring hints that the effects of demand destruction are gaining momentum. At some point, high prices will soften demand so that prices peak, which in turn has broad implications for markets and macro. That tipping point still lies in the future, but given the rapid increase in many key commodities prices in recent months it’s no surprise that hints of demand destruction are starting to emerge.

Monitoring the ebb and flow of forces that will drive demand destruction is always crucial for managing expectations for the economy and markets, but sometimes it’s especially relevant. Now is one of those times, in part because of the unusually sharp increase in certain commodities prices, including energy.

When will demand destruction becomes the dominant force in the economy? Unclear, but we’re close to the apex with each passing day.

Here are some recent examples that suggest the forces of demand destruction are on the rise.

Global economic growth estimates continue to fall. The International Monetary Fund on Tuesday cut its forecast for global growth to a 3.6% increase in GDP for this year and 2023, which marks a 0.8 and 0.2 percentage point slide, respectively, from the estimates published in January. “Global economic prospects have been severely set back, largely because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,” advises Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, economic counsellor at the IMF.

Surging energy costs are driving inflation higher and appear to be pinching discretionary consumer spending. The sharp rise in headline inflation is directly tied to the recent increase energy prices. In turn, the higher costs of producing and transporting a range of goods is starting to show up in consumer spending data. Last week’s US retail sales report shows a strong rise in dollars spent on gasoline, which crowds out spending in other retail sectors. “The Russia-Ukraine shock was a drag on consumer spending in March, with outright declines in spending aside from money spent at gas stations,” says Bill Adams, chief economist for Comerica Bank.

Cameron Dawson, chief market strategist at Fieldpoint Private, a bank, explains that “energy overall is only about 6% of the consumer spending. But when you add other things like food and housing, that jumps to 47% of consumer spending. And so we’re seeing all of these prices rise. So we’re really on the lookout for signs of demand destruction within the consumer. And we’re already starting to see in this earnings season some companies calling out some fraying in that lower income consumer.”

The rise in inflation is driving up mortgage rates and creating headwinds for the housing sector. “We need higher interest rates, at least for a while, to bring inflation down,” writes Paul Krugman, economics professor at the City University of New York Graduate Center. “But higher rates will ‘work’ largely by depressing housing construction, which was already too low.”

“We’re probably going to start to see the beginning of some demand destruction in the housing market because of the rise in mortgage interest rates,” predicts Thomas Simons, a money market economist at Jefferies. “I don’t think it’s enough to really spook the Fed away from their pretty aggressive take on how to address inflation,” he adds, but “it will probably start to give those folks who are talking about a recession in a near-term time horizon, it’ll give them a little more ammunition for the argument and could lead to yields levelling out.”

Meanwhile, “mortgage applications fell for a 6th straight week as mortgage rates surge,” notes Kathy Jones, chief fixed income strategist at Charles Schwab & Co.’s Schwab Center for Financial Research.

China’s slowing economy looks set to cool, which will reduce global demand for commodities. The immediate cause of China’s slowdown is blowback from a rebound in the coronavirus. The government is already downsizing its target year-on-year increase in GDP to 5.5%, a three-decade low.

“If there is a monthly year-on-year real GDP growth measure, we believe it will most likely be negative in April,” predicts Ting Lu, chief China economist at Nomura. He expects “notable downside risks” to the bank’s 4.3% forecast. “We still believe global markets underestimate China’s growth slowdown and supply chain stress, which we feel are set to ripple to the rest of the world.”

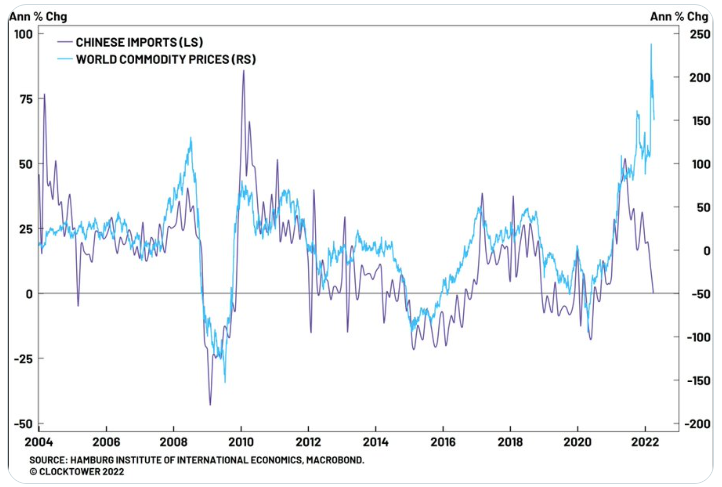

Marko Papic, chief Strategist at Clocktower Group, last week tweeted an intriguing chart that highlights a sharp contrast between rapidly declining Chinese imports and surging commodity prices.

“Everyone in the macro space is fully on board with the Hydrogen Economy: high growth + high inflation = long commodities / short bonds. I mean… that’s my view too!,” he observes. “But then you look at a chart like this… and wonder. Is it time to bet against the consensus?”

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report