Forecasting is a necessary evil in investing. The very act of investing is an exercise in making assumption about future events. If you didn’t expect to book a profit, presumably you wouldn’t make the trade. The trouble starts when you move beyond this basic axiom and start making decisions about how to forecast, what to forecast, and over what time frame. But none of this changes the basic truism that risk is easier to forecast than return. There are caveats, of course, but even small relative advantages can be useful at times.

Yes, the details matter—a lot. For starters, risk comes in a rainbow of colors and so your preference for defining risk will cast a long shadow over your success (or not) in forecasting it. There are also limits related to how far ahead you can model risk. But beggars can’t be choosy and so we must use whatever edges the financial gods have given us.

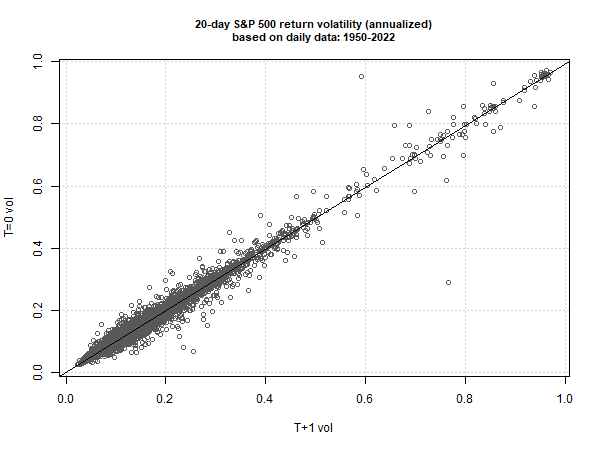

But enough with generalizations. Let’s get specific. As a simple example, consider return volatility, a common if less-than-perfect proxy for risk. To be precise, let’s forecast the day-ahead return volatility for the stock market (S&P 500 Index) using a naïve model that simply uses the previous data point as the ex ante estimate. As the chart below indicates, this is a surprisingly reliable model. Indeed, the correlation between the current day’s risk and its one-day-ahead forecast is a bit more than 0.99, or just shy of perfect correlation, i.e., 1.0.

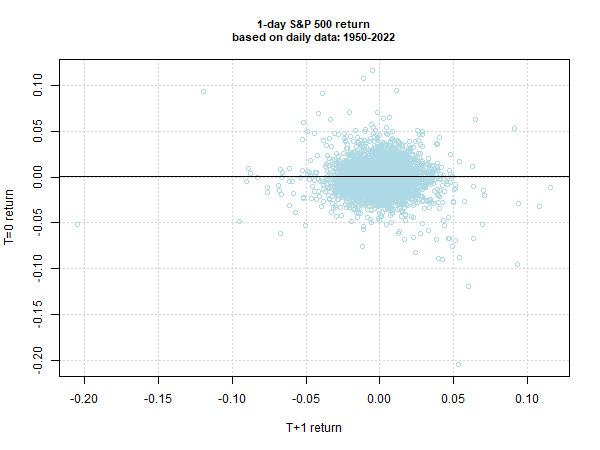

The accuracy of using recent history to forecast risk doesn’t translate to the return side of ledger. Indeed, even on a 1-day-forward basis, yesterday’s S&P 500 performance is essentially worthless as a predictor for today’s return. You might as well flip a coin. This simple fact shows up in the correlation of roughly zero for the two data points through time.

Similarly useless comparisons persist for longer-term comparisons. The lesson: return alone isn’t particularly helpful for predicting itself, at least not with a naïve model. To be fair, we can find more traction by looking for a mean-reversion factor, but that task is a higher level challenge vs. naive risk forecasting.

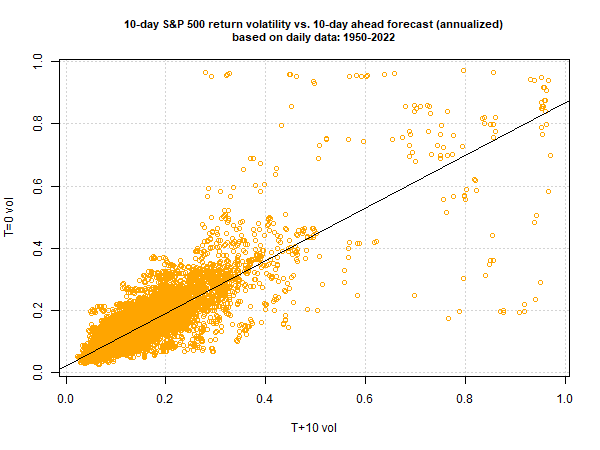

How far out you can push a simple risk forecast before it disintegrates? At ten days forward, there’s still a relatively high degree of correlation (roughly 0.85) between the current print and the ex ante estimate.

Going out to a 20-day forecast cuts the correlation to 0.64. We can see where this is going. There are limits to how far you can extend a naïve risk forecasting model into the future before the results turn into noise — and we reach those limits pretty quickly.

All of which inspires a series of questions: How far ahead is too far for developing useful risk forecasts? Does it vary for different asset classes? Can we enhance the reliability of risk-forecasting effort by using more sophisticated techniques to peer deeper into the future? And why is forecasting risk (or at least return volatility) easier than forecasting performance?

Great questions. In future updates to this series of articles I’ll take a stab at some answers and exploring some of the possibilities for building smarter risk models.

Learn To Use R For Portfolio Analysis

Quantitative Investment Portfolio Analytics In R:

An Introduction To R For Modeling Portfolio Risk and Return

By James Picerno