Judging by the stock market, the odds are rising for a reflationary run. Economic data, however, offer a conflicting view.

Let’s start with stocks, everyone’s favorite discounting machine for guesstimating the future. The S&P 500 Index, after plunging last month at the steepest, fastest pace in the past 70 years, is on a tear following last month’s low. As of yesterday’s close (Apr. 29), the peak-to-trough decline has been pared to relatively modest 13.2% slide—less than half the deepest point in the latest drawdown: -33.9% on Mar. 23.

By the market’s reckoning, the economic rebound will start soon and the snap-back will be dramatic. That would, of course, be great news. But getting from here to there still looks complicated, in part because the US coronavirus data remains volatile, which suggests the timing for a peak in this crisis is still open for debate.

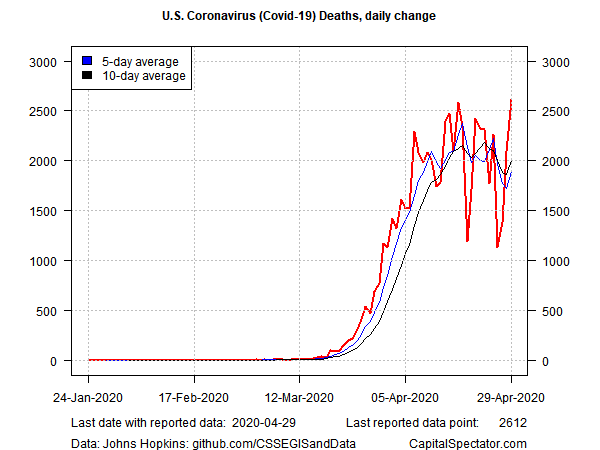

Consider, for example, yesterday’s update on the daily change for new fatalities. According to numbers from Johns Hopkins University, US deaths spiked on Apr. 29 to 2,612 — the highest level since the crisis began.

Meanwhile, the US economy posted its deepest decline in this year’s first quarter since the Great Recession. The 4.8% drop in GDP was deeper than expected and most economists expect an even bigger contraction in Q2.

The dramatic decline in economic activity raises the specter of deflation, or at least a bigger dose of disinflation that temporarily reduces pricing pressure overall to something approaching zero. In yesterday’s monetary policy announcement, the Federal Reserve advised: “The ongoing public health crisis will weigh heavily on economic activity, employment, and inflation in the near term, and poses considerable risks to the economic outlook over the medium term.”

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report

Veteran Fed watcher and economist Tim Duy writes that deflation risk will rise as the shock from the coronavirus fallout continues to reverberate through the economy:

Shutting large portions of the economy resulted in a collapse in spending and surging unemployment. While aid in the form of forgivable loans to small- and medium-sized firms and enhanced unemployment benefits can help keep the basic framework of the economic system glued together, it won’t solve the fundamental problem that economic activity requires actual customers. No customers, no firms. No firms, no employment.

He worries, too, that “not only do we have a collapse in demand, but the eventual rebound in activity is likely to be anemic, too.”

It all adds up to a rising risk of deflation. The question is whether the Fed, along with fiscal support from Congress, can offset this risk through effective policy decisions? Perhaps, although given the unprecedented nature of the recession and the hazy outlook on how the crisis ends leaves more questions than answers.

Despite the risks, some analysts worry that inflation will come roaring back, courtesy of the government’s massive stimulus efforts in recent weeks. That’s a possibility… eventually. But a strong rebound in pricing pressure would first require a solid and sustained economic rebound. If you haven’t noticed, that happy change in the macro trend is nowhere on the horizon at this point.

True, some forecasters see a strong revival in economic activity for Q3. Perhaps, but we first have to go through the Q2 devastation and it’s unclear how or if the April-through-June contraction will change the outlook and alter economic assumptions.

Meantime, the Treasury market has cut its inflation outlook recently, based on the implied forecast via the yield spread on nominal less inflation-indexed securities. Five-year Treasuries, for example, have been pricing in inflation below 1% for weeks–well below the 1.5%-plus estimate that prevailed in late-2019. Keep your eye on this data for a measure of how the crowd is pricing in deflation risk. If the forecast takes a dive in the weeks ahead, that would be a worrisome sign.

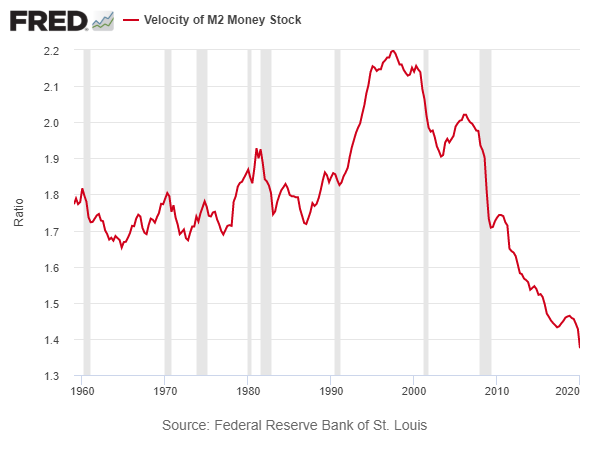

Perhaps a bigger worry, as Trevor Jackson observes, are signs that “the relation between the money supply and inflation was breaking down,” even before the current crisis. Central bankers, writes the assistant professor of economic history at George Washington University, “had been running as fast as they could just to stay in the same place. Economists (and The Economist) began to wonder if inflation was over or had lost all meaning.“

Some dismal scientists say the smoking gun is the downside trend in the velocity of money, which has been sliding since the 2008-2009 recession (see chart below). This measure of how frequently money changes hands is a key component for deciding how likely inflation will heat up or cool down. By some accounts, until velocity pulls out of its long-running dive, disinflation/deflation will remain the path of least resistance. That’s old news, of course. What’s new is whether the coronavirus recession kills whatever’s left of inflation.

The stakes are high, reminds the Financial Times, in part thanks to the runup in debt over the past decade:

‘Deflation would make high corporate and government debt loads even harder to manage as interest payments stay fixed but wages, prices and tax payments all fall in cash terms. All this suggests that investors should prepare for another long period of miserable yields on government debt — most likely below inflation.”

Learn To Use R For Portfolio Analysis

Quantitative Investment Portfolio Analytics In R:

An Introduction To R For Modeling Portfolio Risk and Return

By James Picerno

Pingback: Deflation Risk Increasing? - TradingGods.net