Before the coronavirus shock, inflation in the US appeared tame by the standard measures. But the macroeconomic earth has shifted in recent weeks to combat the fallout from Covid-19. The Federal Reserve has announced unlimited asset purchases and is running ultra-dovish monetary policy. Meanwhile, the federal government is about to roll out a new $2 trillion stimulus package. It all adds up to what is perhaps the most ambitious effort in history to grease the economy’s wheels (or at least prevent collapse). Is this herculean effort also laying the groundwork for higher or even soaring inflation?

The experience of the past decade leaves plenty of room for humility in predicting what comes next for pricing pressure. The hyperinflation that many pundits thought was fate in the wake of the Fed’s extraordinary monetary stimulus following the 2008-2009 crisis never materialized. Will it be different this time? No one knows, although the hyperinflation warnings have returned anew in the wake of the latest policy changes.

Peter Schiff, a perennial doomsday pundit and gold bug at Euro Pacific Capital, predicts that the latest changes in Fed policy “ensures that this recession, depression that we’re entering is going to be extremely brutal in the inflation that is going to ravage the economy, particularly investors and retirees.”

Hyperbolic? Yes, especially when you consider that surging inflation forecasts by Schiff and others have been wrong all along. But has something finally changed to turn extreme predictions into realistic estimates? Unclear, although inflation sentiment via the Treasury market’s implied forecast appears to be reviving, albeit modestly so far, after an extended disinflationary run.

How is recession risk evolving? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report

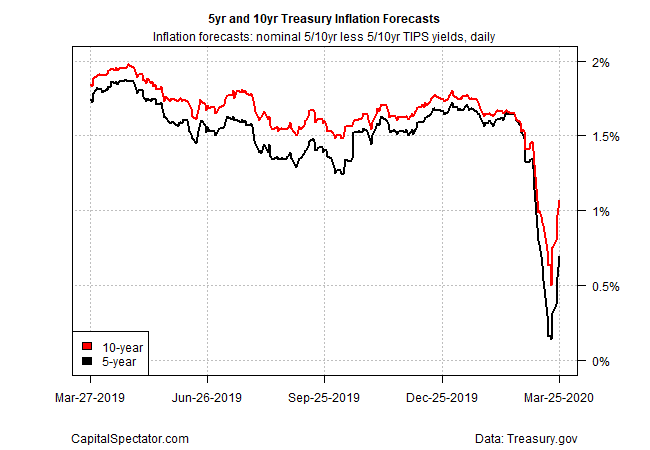

The yield spread for nominal less inflation-indexed Treasuries had been falling sharply in recent weeks, threatening to go negative at some point. The 5-year’s inflation estimate, for instance, dropped from roughly 1.6% in late-February to just 0.14% on March 19. But in recent days, the spread has bounced, rising to 0.69% on Wednesday (Mar. 25), based on daily data via Treasury.gov.

Is this an early sign that inflation is poised to surge? Eric Stein, co-director of global income at asset manager Eaton Vance, is skeptical. “The lesson from 2008 is that we had a fair amount of fiscal stimulus and monetary stimulus and people thought we were getting hyperinflation, and that clearly didn’t happen,” he says. He expects inflation will eventual revive but stick just below the Fed’s 2% target after the coronavirus risk fades.

But there’s no shortage of investors with a darker outlook. Charlie Morris, a multi-asset fund manager at Atlantic House, tweeted earlier this week that the Treasury TIPS “market now thinks long term inflation will return with vengeance. It was a very different picture last week!”

Other analysts say stagflation risk is bubbling—slow or no growth combined with relatively high inflation. Victor Li, professor of economics at Villanova School of Business, advises that while the economy will take a hit in the short run, “the decline of both demand and supply means that we should not expect to see the falling prices and deflation that occurred during the Great Recession and Great Depression.”

He predicts “there will be a surge in demand as fear abates, customers return to shopping centers and restaurants, and businesses and consumers look to borrow at historically low interest rates. Ultimately, the imbalance will create a lopsided recovery with slow output growth with accelerating prices and inflation; in other words, stagflation.”

Inflation, in fact was already showing a modest upside bias in recent months—before the coronavirus exploded into a full-blown global crisis, based on one-year changes in core and headline consumer inflation. The next several months for updates could be telling for deciding if pricing pressure is headed higher on a sustained basis–or not.

There’s also concern that rising federal debt will help drive inflation higher. As the Brookings Institution notes, “at some point, if central banks create too much money, they will produce an increase in inflation–too many dollars chasing too few goods–or they will have to raise interest rates to slow the economy to restrain inflation. We are not yet at that point, though.”

Note, however, that federal debt has ballooned in recent years as percentage of the economy, a shift that encourages if not quite ensures higher inflation. With trillions in new government spending pledged, the red ink trend isn’t about to go into remission any time soon. As the Brookings Institution observes: “federal debt is more than twice what it was before the Great Recession (80 percent of GDP today vs 35 percent at the end of 2007) and larger than at any time in US history except immediately after World War II. We are going to bust that record, for sure.”

Will any of this matter for the inflation? Probably, although in what degree is an open question. But with the economic outlook clouded on multiple fronts in the wake of recent events, confidence is low on what happens next.

One thing that appears certain: red ink in the extreme on government balance sheets is here to stay. For good or ill, Stephen Jen at Eurizon SLJ Capital, says “large fiscal deficits fully underwritten by central banks” will become the new normal.

Learn To Use R For Portfolio Analysis

Quantitative Investment Portfolio Analytics In R:

An Introduction To R For Modeling Portfolio Risk and Return

By James Picerno