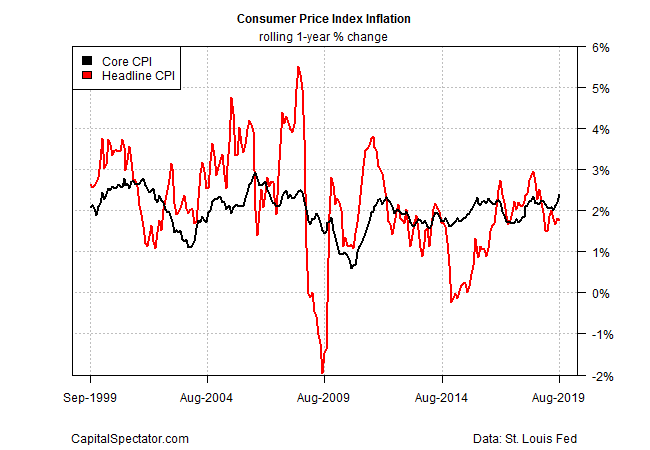

Just when it looked like inflation’s threat was fading, yesterday’s August report on consumer prices dispensed a not-so-fast alert. The core reading of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which excludes food and energy, rose 0.3% last month and accelerated to a 2.4% annual pace – the highest in 11 years. One data point isn’t a trend, of course. But yesterday’s release is conspicuous at a time when the US economy is struggling with slow growth and expectations that interest rates are headed lower, perhaps turning negative at some point.

Core CPI has a history of dispensing relatively reliable forecasts of inflation’s future path and so this data isn’t easily ignored. If this measure of pricing pressure continues to tick up in the months ahead, the trend will complicate and perhaps even derail the Federal Reserve’s plans to loosen policy.

For now, the crowd is still expecting a rate cut at next week’s FOMC meeting (Sep. 18). Fed funds futures are pricing in a roughly 87% probability this morning that the central bank will trim its target rate by 25 basis points to a 1.75%-to-2.0% range. Deciding what happens beyond next week’s announcement, however, is suddenly open for debate in the wake of yesterday’s CPI data.

The key driver in the core inflation’s latest pop stems from health care. As Bloomberg notes:

The core reading reflected the biggest monthly rise

in medical-care costs since 2016 and record increases in health-insurance

prices. Sustained increases in inflation could give some Federal Reserve policy

makers pause as they weigh additional interest-rate cuts this year, though the

central bank is expected to make a second straight reduction next week as the

global growth outlook dims and uncertainty over trade policy damps business

investment.

Adding to the upside pressure on prices is the US-China trade war. Although both sides have made gestures this week to soften the conflict, the recently imposed tariffs have lifted import prices.

Analysts at ING advise that “there is the potential for the latest round of tariff hikes, which tended to be focused on consumer goods, to be passed on in prices. This means core inflation is likely to remain elevated and therefore consistent with the Fed’s mandate. On the face of it, this has the potential to limit the scope of additional Federal Reserve rate cuts.”

Is Recession Risk Rising? Monitor the outlook with a subscription to:

The US Business Cycle Risk Report

The upward bias in core CPI isn’t inherently troubling, at least not yet. The problem is that higher pricing pressure is accompanied by softer economic growth. Earlier this week, The Capital Spectator’s median estimate for the upcoming third-quarter GDP report (based on a set of nowcasts from various sources) is a sluggish 2.0%.

By some accounts, the core CPI jump looks like a wake-up call. “Concerns about too-low inflation appear misguided,” notes Sal Guatieri, a senior economist at BMO Capital Markets. “The Fed will still cut rates next week to provide added insurance in the event that the trade war escalates, but it might think twice about moving again in October if core inflation shows any further spark.”

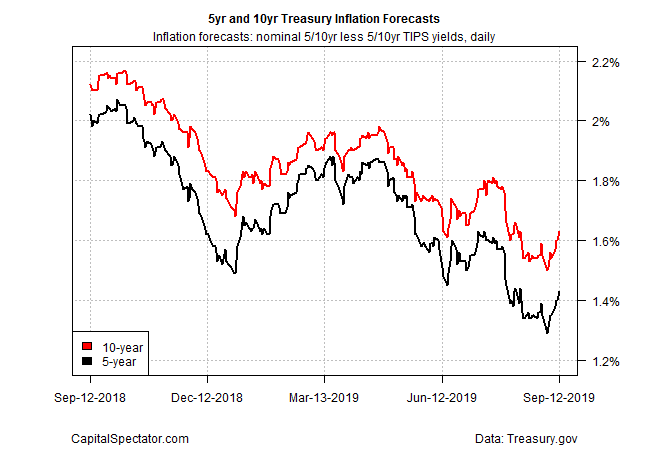

Meantime, the bond market is discounting, on the margins, the potential for firmer inflation going forward. After an extraordinary slide in the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield last week, the crowd is rethinking its rush into government bonds, at least partly. After sliding to 1.47%, the 10-year rate has reversed course in recent day, rising to 1.79% at yesterday’s close—the highest since Aug. 2 (based on daily data).

The question is how much noise are we looking at in the latest pop in core CPI? Unclear, although one or two additional inflation updates may clear things up. In the interim, keep your eye on the Treasury market’s implied inflation forecasts via the yield spreads on nominal less inflation-indexed securities. The spread for the 5-year maturities, for example, has jumped in recent days, but at 1.43% it’s clear that the market is still anticipating weak inflation.

But the hard data on pricing pressure is hinting at the possibility that inflation is far less quiescent than assumed. Yes, the jump in core CPI in August could be an anomaly. If it isn’t, the Fed’s facing a much tougher challenge because it will be forced to navigate between two conflicting extremes: slowing growth and rising inflation, a.k.a. stagflation—a central bank’s worst nightmare.

In that scenario, the obvious policy decisions are almost always “wrong.” Raising rates threatens to push the economy into recession. By contrast, easing policy to juice growth risks creating runaway inflation. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

The last time stagflation was a problem was the 1970s. Not surprisingly, the decade was one of the Fed’s low points for effective policy decisions. Will this time be any different if we’re heading into a new run of stagflation?

Learn To Use R For Portfolio Analysis

Quantitative Investment Portfolio Analytics In R:

An Introduction To R For Modeling Portfolio Risk and Return

By James Picerno

Pingback: Is Inflation Rising? - TradingGods.net