The Federal Reserve on Wednesday hiked interest rates again, asserting that moderate economic growth will continue for the foreseeable future. But confidence appeared to be in short supply via the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield, which slumped amid rising demand for this safe-haven asset.

Tighter monetary policy doesn’t usually promote a robust round of bond purchases, but yesterday’s trading broke with tradition. The 10-year yield fell for the first time in over week, dropping six basis points to 2.15% yesterday (June 15), close to a seven-month low, based on daily data via Treasury.gov. As recently as mid-March, the 10-year rate was above 2.60%.

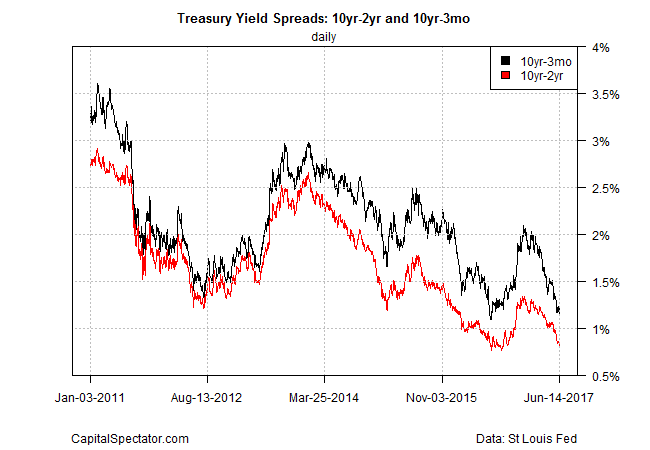

The latest slide in the 10-year continued to squeeze the yield spread. The widely followed 10-year/2-year spread, for instance, fell to 80 basis point, the lowest since last September.

The net result: a flatter Treasury curve generally. The shift is conspicuous this year, with short rates up to the 2-year maturity rising year to date while yields for 5-years-plus maturities have fallen since last year’s close.

A flatter yield curve has traditionally been a warning sign for the economy, although only an inverted curve – short rates above long rates – is an outright danger sign that a new recession is near. By that standard, the Treasury market is currently forecasting softer growth but no recession.

Fed Chair Yellen reasoned that raising interest rates – yesterday’s increase lifted the central bank’s benchmark by a quarter point to a 1.0%-to-1.25% range – is warranted due to ongoing economic growth. Yesterday’s decision “reflects the progress the economy has made and is expected to make toward maximum employment and price stability,” she explained in a press conference.

But she also left the impression that the Fed is eager to raise rates, in part, to preserve the ability to cut when the next recession strikes. The rationale is also bound up with the logic that leaving rates too low for too long might back the Fed into a corner if economic growth and/or inflation accelerates, which would force a series sharp rate hikes in a relatively short period. In turn, that could trigger a recession, Yellen said. Gradually raising rates, by contrast, minimizes the danger.

One could interpret that line of thinking as an admission that current economic conditions don’t merit a rate hike. There’s certainly some evidence in support of that view. Headline consumer price inflation in May fell below the Fed’s 2.0% target for the first time in six months. “The latest inflation data have undoubtedly helped the case of officials arguing for waiting more than three months for the next move,” noted Jim O’Sullivan, chief US economist at High Frequency Economics.

Meantime, the Fed’s revised median inflation forecast for all of 2017 was cut in yesterday’s release of new quarterly economic forecasts. The central bank is expecting a 1.6% increase in headline inflation this year, down from the 1.9% outlook published in March. The Fed also trimmed its median prediction for core inflation in 2017 to 1.7% from 1.9% previously.

Meanwhile, the Fed’s estimate of economic growth for this year edged up slightly to 2.2% from 2.1%. Forecasts from other sources also anticipate that moderate growth will prevail for the near term. This month’s survey of economists via The Wall Street Journal, for instance, points to a pickup in growth for the rest of the year after a weak 1.2% GDP rise in the first quarter.

The bond market, however, is anxious. It’s premature to ring the alarm bells – the near-term outlook for the economy still shows that the probability of a recession is virtually nil. But a yield curve that continues to flatten would be worrisome.

Yellen and company are effectively arguing that the bond market is wrong. The downshift in inflation is probably temporary, she said yesterday. Meanwhile, the economy remains on track for a moderate if unimpressive rate of growth. There’s a reasonable case to agree. But until the bond market’s on board with that outlook, skeptics will wonder if the Fed’s monetary policy is raising recession risk.

Pingback: Federal Reserve Asserts Moderate Economic Growth Will Continue in Spite of a Rate Hike - TradingGods.net

Pingback: Weekend Reading: Charged With Obstruction | RIA

Pingback: Landmark Links June 16th – Back to the Future

Pingback: Weekend Reading: Charged With Obstruction | NewZSentinel

Pingback: Weekend Reading: Charged With Obstruction | Wall Street Karma

Pingback: Elliott Wave Analytics » Blog Archive Weekend Reading: Charged With Obstruction